January 20th – Little Orme – Upper reaches

I‘d spent longer watching the seals than I had intended, so almost talked myself out of doing some proper walking and heading up to the summit. It was cold, the sun was already sinking lower in the sky and I knew the upward tracks were going to be muddy. But one of my aims for this outing had been to check to see whether or not the cormorants had begun nesting yet, so onwards and upwards it was.

At the bottom of the steep upward slope, Rabbit Hill to locals, a bird sat perfectly still at the top of a smallish ash tree. The sun in my eyes was so bright I could only see it as a black shape, so made another assumption that as this is about the highest point on this windswept clifftop and a favoured perch for crows, magpies and jackdaws, that it was a corvid. Only when I lightened up the photograph I took did I realise it had been a Kestrel.

The bracken and brambles that covered the slope to the landward side of the track have been cut back hard; this vegetation provides cover for a variety of small birds, including resident Stonechats and Whitethroats that come here for the breeding season. I’m sure it will have grown up again by the time they arrive.

I was right about the mud! It was almost take one step forward and slide back two. I pictured my walking pole lying uselessly in the boot of my car. I should use it more often, but it gets in the way when I want to stop and take a photograph. I took a breather to turn and photograph the view; no matter the number of times I have done it, it’s just so amazing I can’t resist. The spit of land projecting finger-like into the sea is Rhos Point and despite the hefty sea defences I know it has in place, it looks so vulnerable from here, perhaps more so to me because it’s where my daughter and her family lives and I can pick their house out from here!

At the top of the slippery slope is a levelled area where much of the stone was quarried out. The cliff wall at the back of this now grassy area is Jackdaw city, with many pairs of birds nesting in its nooks and crannies. You realise how many of them there are when the Buzzards glide into the airspace above and numbers of them suddenly zoom up and surround them, determinedly driving it away while making a heck of a racket.

(click on image to enlarge)

Herring gulls often join in the mobbing party too; it may seem that they prefer roofs and chimneys to nest on, but some do prefer the more traditional option of a bit of cliff. It’s interesting that although they may rob other birds of their eggs and chicks, they’ll join forces to drive off any potential predators of theirs. It’s not too clear from my photograph who’s who, but one Buzzard is very slightly left of centre and the other approaching the far left, with defending birds approaching mainly from the right. Poor old Buzzards, every other bird picks on them, even much smaller Starlings!

The edge of the cliff is crumbly and eroding but is a favourite spot for Jackdaws to sit and look down on the lower levels of the headland. There were several pairs sitting doing just that this afternoon, probably ones with nest sites nearby on the cliffs of the lower level.

I took a photograph looking down into Angel Bay from up here; it looked as though quite a number had moved off.

One of my favourite sights is golden gorse flowering against the background of a blue sea.

One of my favourite sights is golden gorse flowering against the background of a blue sea.

It’s always sad when a tree dies, but the skeleton of this Elder is now beautifully adorned with lichens and a fungus, which I’m sure is now past its peak. I’m not great on fungi, but I do know the one most closely associated with the Elder is Jew’s ear or jelly ear Auricularia auricular-judae; is it that Annie? I wish I’d seen it earlier.

The grass up here is grazed by sheep and further nibbled by rabbits, so is always neat and well-groomed. The path curves into this small clearing that looks almost like a cleverly landscaped wild garden designed to lead you to the stunning vista.

click on image to enlarge

The nearest rounded hill is Bryn Euryn which I’ve walked you around many times and shown views from there to here, but you can see they would be a fairly short flight away from one another for Buzzards, which nest on Bryn Euryn, and Ravens which regularly overfly both.

Some of the hawthorns here still have good crops of berries.

And there is lots of glorious golden fragrant gorse.

Another wider view from higher up over Colwyn Bay and towards the Clwydian Range of mountains where Offa’s Dyke begins.

click to enlarge

The low sun gives a wonderful texture to the rough grass and rocks. I always wonder how rocks such as this one arrived where they are, but this one I use this one to recognise the point where I leave the path and approach the cliff edge, extremely cautiously, to get a better view of the site of the cormorants’ colonial nesting site.

They don’t appear to be doing much yet, in fact there were just two there when I first looked, although a few more did fly in to join them as I watched.

The Great Orme – click to enlarge

I climbed up a bit higher to admire the view across Llandudno Bay to the Great Orme. The pier looks toy-like against its great bulk.

The sun had dropped further and was almost hidden by the highest part of this headland to my left. The view from here is across Llandudno town to Anglesey and the bulky headland of Penmaenmawr. If you were looking at this as a walker of the Wales Coast Path travelling in this westerly direction, you could roughly trace your onward path and see where you would be in a day or so’s time.

Llandudno Bay, town and beyond – click to enlarge

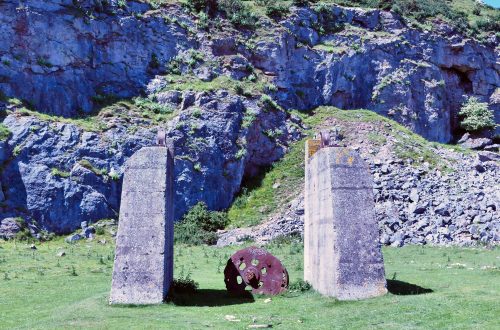

Low light lends a different atmosphere to this place, especially when you’re alone and have an imagination such as mine. Rocks cast shadows and a solidity not as apparent in bright sunlight. I wonder how it looked before its bulk was reduced by quarrying? Are these squared off rocks remnants from that time or were they deliberately placed before then for some other purpose.

The remnants of a dry stone wall lead the eye to the wonderful view.

click to enlarge

Then there are Hawthorn trees, contorted into wonderful shapes by the strong prevailing winds and features long associated with tales of witches and magic……

Even in broad daylight I wonder about the spot in the image below. I can easily imagine as some kind of mystical meeting place guarded by the trees and I know that as a child I’d have found a way around the fencing and sat on the top of that little hummock letting my imagination run riot, most probably giving myself nightmares.

I fancy other mystical markers – a hawthorn branch heavily covered with lichen that reaches out over the track and frames the view.

and a little tree well covered with lichens and further embellished with sheep’s wool.

The atmosphere is further enhanced by a pair of Ravens, companions of witches and wizards, ‘gronking’ as they passed overhead.

And a rabbit, moving strangely slowly around behind the wire fence. It didn’t bounce away from me like rabbits usually do and I wasn’t sure if it was just old or not well; its eyes looked strange and it may not have been seeing properly, if at all. It put me in mind of rabbits we used to see years ago with Mixomatosis, but is that still around? (see footnote)

A chaffinch foraging around in the gorse and blackthorn scrub led my eye to this sunlit spider’s web and distracted me from further over-imaginative thoughts!

Had a bit of a slithery walk down Rabbit Hill then headed back to leave the site. I took the path closest to the cliff edge to avoid oncoming late afternoon dog-walkers and spotted this bird sitting on the top of a gorse bush seemingly looking out to sea. Once again the sun was obscuring it from proper view but there was no mistaking this was a Kestrel, a young one I think. It was very cold now but the bird was sitting perfectly still with its feathers fluffed out.

I risked walking back around to get some better lighting, expecting it to fly off, but although I think it was aware of me it stayed put. I did get to a point with a better view – and the camera battery died! Time to go.

More about Myxomatosis

When I wrote this post and mentioned the ‘poorly’ rabbit I had seen, I hadn’t realised that the horrible disease, Myxomatosis, was still present and affecting rabbit populations in the UK. As a country-bred child back in the ’60s, I remember seeing many affected rabbits which I found distressing, and as the poor rabbits were sick they were easily caught by our cats, who didn’t kill them, but did bring them home. I also didn’t know then that it could be passed on to pet rabbits; now they must be vaccinated against the disease.

The disease called Myxomatosis reached the UK in 1953, where the first outbreak to be officially confirmed was in Bough Beech, Kent in September 1953. It was encouraged in the UK as an effective rabbit bio-control measure; this was done by placing sick rabbits in burrows, though this is now illegal. As a result, it is understood that more than 99% of rabbits in the UK were killed by the outbreak. However, by 2005 – fifty years later – a survey of 16,000 ha (40,000 acres) reported that the rabbit populations had increased three-fold every two years, likely as a result of increasing genetic resistance, or acquired immunity to the Myxomatosis virus. Despite this, it still appears regularly at rabbit warrens.

If you’ve never seen an affected rabbit, I can’t stress how awful it is. Initially the disease may be is visible as lumps (myxomata) and puffiness around the head and genitals, which progresses to acute conjunctivitis and possibly blindness; this also may be the first visible symptom of the disease. The rabbits become listless, lose appetite, and develop a fever. Secondary bacterial infections occur in most cases, which cause pneumonia and purulent inflammation of the lungs. In cases where the rabbit has little or no resistance, death may take place rapidly, often in as little as 48 hours; most cases result in death within 14 days. Not a good way to die.

Wild rabbits tend to recover quickly once the disease has passed; a certain density of rabbits is needed to keep the disease going and once the number of rabbits drops below that level the disease will disappear until the rabbit numbers increase again.